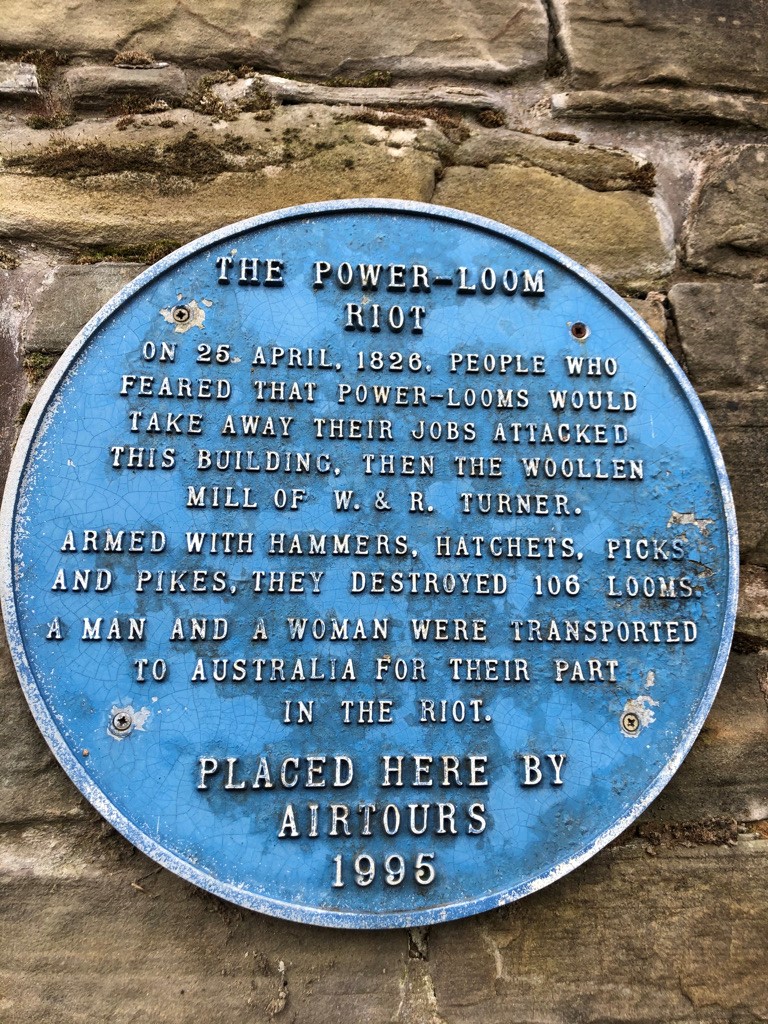

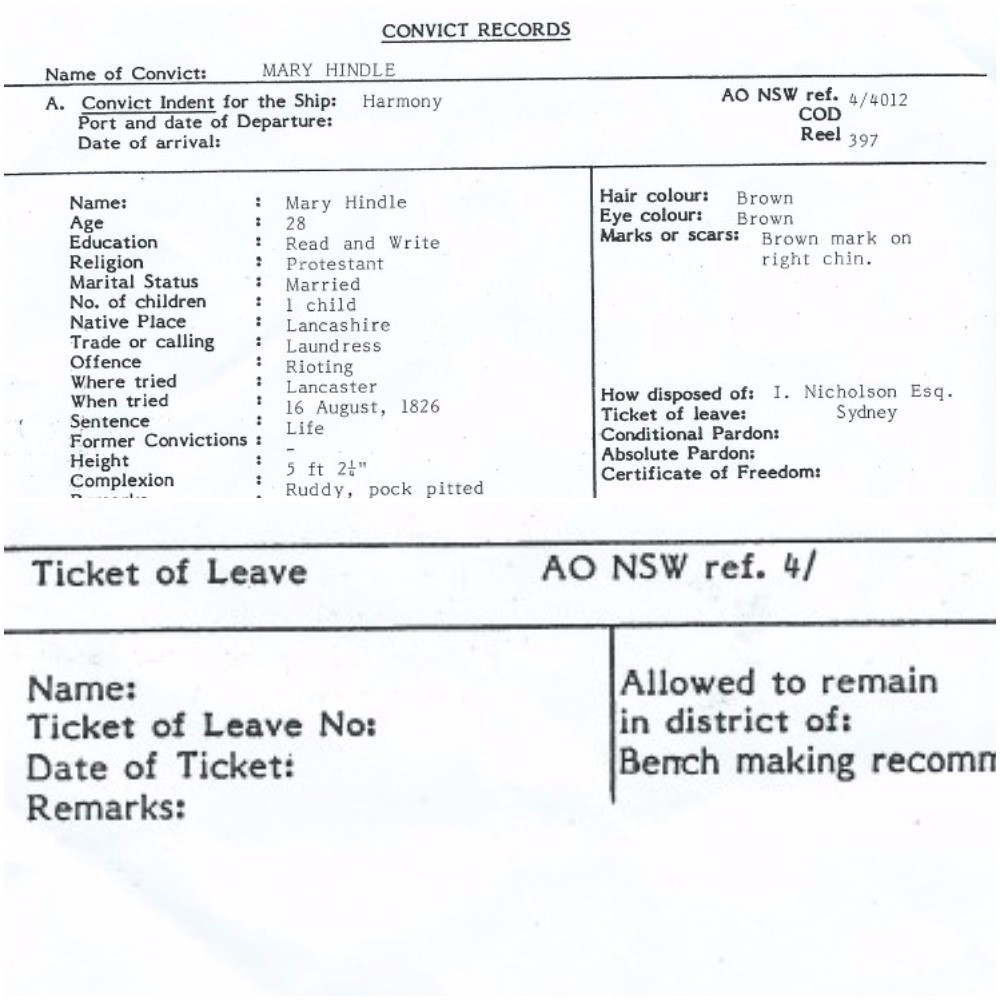

As part of our International Women’s Day 2021 events we are sharing this account of Rossendale woman, Mary Hindle who was deported to Australia in 1827 after being convicted of involvement in The Power Loom Riot of 1826.

Our SI Rossendale member, Patricia Calway has re-told this sad story of injustice for us.

My story – Mary Hindle, Todd Hall Haslingden

“My name is Mary Hindle, I left England on board the prison ship Harmony in 1827 bound for Australia. Exciting you might think, but not for me.

I lived in Haslingden, Lancashire, and was married to James a handloom weaver in May 1798. A good, handsome man of tall stature and a loving nature. We lived in a tenement with other home weavers at Todd Hall. We were blessed with one daughter Elizabeth and other children, but they didn’t survive. We worked hard but we often went hungry. At least we had a roof over our heads.

I remember the 1820s as terrible years. I lost my Mum in 21, she was only 48, God bless her. Then in January 22, we lost our son Abraham. He was only one. As was Robert, who we lost December 1823 and then to cap it all, my Dad in September 24 at the old age of 45. Times were tough for all weavers. At least we kept Elizabeth.

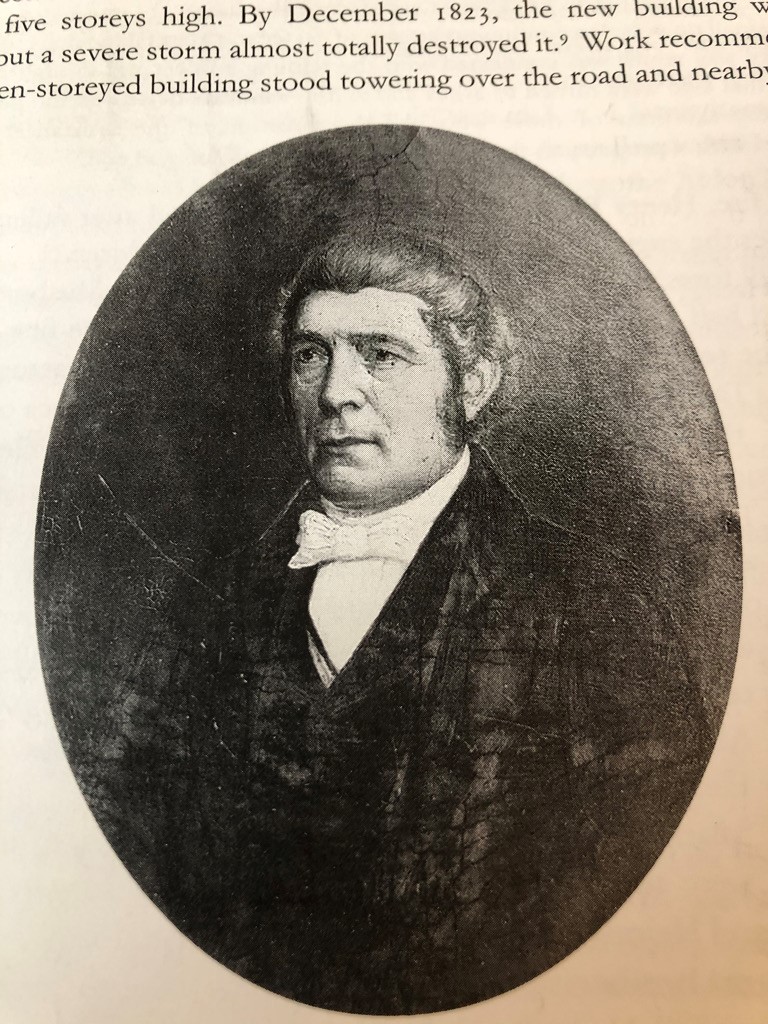

Trouble was coming though, weaving machinery called power looms were being introduced into newly built woollen factories. William Turner our current employer had just built Middle Mill down the road. A five -story mill building made of stone where he would put power looms. These power looms would replace us home weavers and do us out of our livelihood. No money for food or rent. How would we live?

I’ll never forget Tuesday 25 April 1826. There was talk of weavers gathering together to shout against the new power looms. I couldn’t find Elizabeth, so I wandered down there to make sure she was not caught up in any trouble.

It was a rough scene, men armed with hammers, hatchets, picks and pikes and a shed load of anger, broke into the mill and smashed 106 power looms! I stayed outside and kept out of trouble, but it was a terrible sight to see. Anyhow Elizabeth was safe.

Then things went from bad to worse, next day the Peelers came and arrested me for rioting! An employee of William Turner accused me of being inside the mill and “shouting encouragement to the rioters”. There I was NOT. Thirty -five men and six other women were arrested.

It was a terrible trial. The judges were out for blood to teach us all a lesson and it mattered not what anybody said. Something to do with the Industrial Revolution, whatever that is. Even my employer William Turner himself spoke up for me, but it was no use. Thirty-five men and six women, including me, were sentenced to death. Death!!!

A month later after a lot of pressure from our employers, the sentences for eight men and 2 women me included, were commuted to transportation for life, to New South Wales, Australia. The others were given short prison sentences. I could n’t believe it. I shouted my innocence and cried and cried but it made no difference. William Turner even petitioned Robert Peel, the Home Secretary and still no joy.

A month later after a lot of pressure from our employers, the sentences for eight men and 2 women me included, were commuted to transportation for life, to New South Wales, Australia. The others were given short prison sentences. I could n’t believe it. I shouted my innocence and cried and cried but it made no difference. William Turner even petitioned Robert Peel, the Home Secretary and still no joy.

So heart broken and dejected I bade farewell to my handsome man and beautiful daughter and set sail, in the prison ship with hundreds of others. The journey was terrible and conditions worse than at home. I was ill for most of the time but a kind ships ‘doctor looked after me and said I had pleurisy. The journey took six months and when we landed, I could hardly stand.

So heart broken and dejected I bade farewell to my handsome man and beautiful daughter and set sail, in the prison ship with hundreds of others. The journey was terrible and conditions worse than at home. I was ill for most of the time but a kind ships ‘doctor looked after me and said I had pleurisy. The journey took six months and when we landed, I could hardly stand.

On arrival in September 27, I was assigned to the Nicholson family as a laundress, hard work but at least I was warm and fed. I repeatedly asked whether a pardon had come through, because everyone knew I was innocent, and William Turner said I should NEVER give up hope.

I stayed there until I got a “Ticket of Leave” in 31. This was only given for good conduct and exempted me from working for a particular employer, provided I remained in the district of Sydney. Surely, they would issue a pardon now. No, so I did not give up hope and carried on working hard and I received another “Ticket of Leave” in 35.

I changed jobs then and carried on working as a laundress, but my spirits were low, and I was starting to give up hope. I decided to run away.

I was caught quickly of course and was sent to the Parramatta Female Factory. You don’t want to know what happened there. Enough to say, it was worse than prison and the punishment was harsh. I decided I would have one last attempt at obtaining a pardon. I wrote to the Governor but got the usual stock reply, no. Now I am at a really low ebb, I wrote a letter home giving everyone my love. Actually I did not write it because I cannot write but a kind woman wrote it for me.

I was let out in 40 and worked again as a laundress for Thomas Ryan, the Chief Clerk to the Principal Superintendent of Convicts. Thomas Ryan was an ex-convict himself in Sydney. I ran away again, was soon caught and was put back in the dreaded Parramatta Female Factory.

This time I knew I was not coming out. So on this day 21 August 1841 let me say farewell. There is no point in this life any longer.”

Epilogue

And so ended fifteen years of imprisonment and transportation with all the horrors that went with both. A good woman who had endured so much, came to a very sad end.

According to her former employers, Mary had ‘uniformly borne a good character for peaceable demeanour, honesty and industry’ and ‘very few have come so clean and descent and none have done their work better’

1820s was the start of the Industrial Revolution. Mary’s sentence was a warning to all others. She was an example of a descent woman who was deported to Australia in order to put fear in the hearts of all other potential rioting weavers.

She was buried without a headstone in Parramatta graveyard, Sydney.

This is based on a true -life story.

Research source – Lorraine Hooper (with added information from William Turner c2000). Haslingden Old and New.

Contact SI Rossendale

If you’d like to join our group of women, raising money for charity and finding friendship, then get in touch with us.

Alternatively, you can follow us on social media via Facebook or Twitter.