I thought the way to start this blog would be to define what sexual abuse is, and how it is defined in the UK. That turned out not to be so easy – when I googled it, the first definition was from NSPCC, then the Northern Ireland Government (which I thought was good, given devolved administrations’ responsibilities), the Metropolitan Police, and then there were a variety of others, but the first reference I could find from UK government was in a fact sheet for the Domestic Abuse Bill 2020.

So, I turned to the UN website, where sexual abuse is defined as –‘any sexual or sexually motivated behaviour that is done to someone without that person’s consent or understanding. It can be online or in person, and it can happen to anyone. It includes a range of sexual acts, such as unwanted touching, forced oral sex, rape, or voyeurism’.

One type of sexual abuse that people have become more aware of over the last few years is Female Genital Mutilation (FGM), with the UN designating 6 February as the International Day for Zero Tolerance for Female Genital Mutilation.

Again, I referred to the UN website, which defines FGM as –

‘’all procedures that involve altering or injuring the female genitalia for non-medical reasons and is recognized internationally as a violation of the human rights, the health and the integrity of girls and women”.

FGM leads to short-term complications as well as long-term consequences for their girl’s sexual and reproductive health and mental health.

Although primarily concentrated in 30 countries in Africa and the Middle East, FGM is a universal problem with immigrants taking the practice to western countries. Scotland South President Aileen remembers as a student nurse, a Sudanese nurse telling her about the practice nearly 50 years ago.

Over the last 25 years, the prevalence of FGM has declined globally. Today, a girl is one-third less likely to undergo FGM than 30 years ago.

Although illegal in the UK, FGM takes place here, or girls are cut while on holiday, back visiting relatives. London has the highest incidence of FGM in the UK, and that was where the first successful conviction in UK took place in 2019.

Another positive step forward I have discovered that a group of female Kenyan students have developed an app, iCut, to help girls in Kenya. They can use the app either to alert authorities to potential cutting, or to get medical help for girls who have been cut.

FGM is unusual in that the perpetrator is usually female, but any discussion about sexual abuse must include men. Men must take responsibility for ending sexual violence by changing their attitudes and behaviours towards women as well as challenging those of their peers.

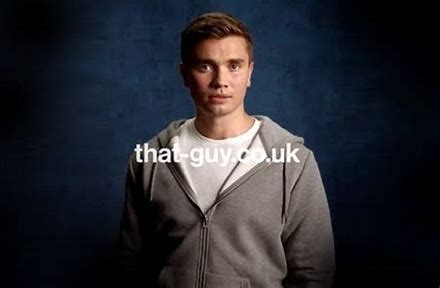

Police Scotland have gained plaudits for their ‘Don’t be that guy’ advertising campaigns. The first in 2021 concentrated on getting men to recognise their own behaviour, and the changes they needed to make. The 2022 campaign asked men to challenge to their friends, or other men, when they were displaying abusive behaviour, even just what they were saying to women.

You can watch the videos on YouTube – http://youtu.be/sVcu8Hwv8u8

These are just a few initiatives, both in UK and abroad, that hopefully will help the UN meet its target of eliminating FGM by 2030.

There are lots of organisations that offer support for victims of sexual abuse in the 4 countries of the UK. For example, Rape Crisis.

In Scotland – www.rapecrisisscotland.org.uk

Phone – 08088 01 03 02

In Northern Ireland – www.rapecrisisni.org.uk

Phone – 08000 0246 991

In England & Wales – www.rapecrisis.org.uk